The Haunts of the Soul

1Have mercy on me, O God,

because of your unfailing love.

Because of your great compassion,

blot out the stain of my sins.

2Wash me clean from my guilt.

Purify me from my sin.

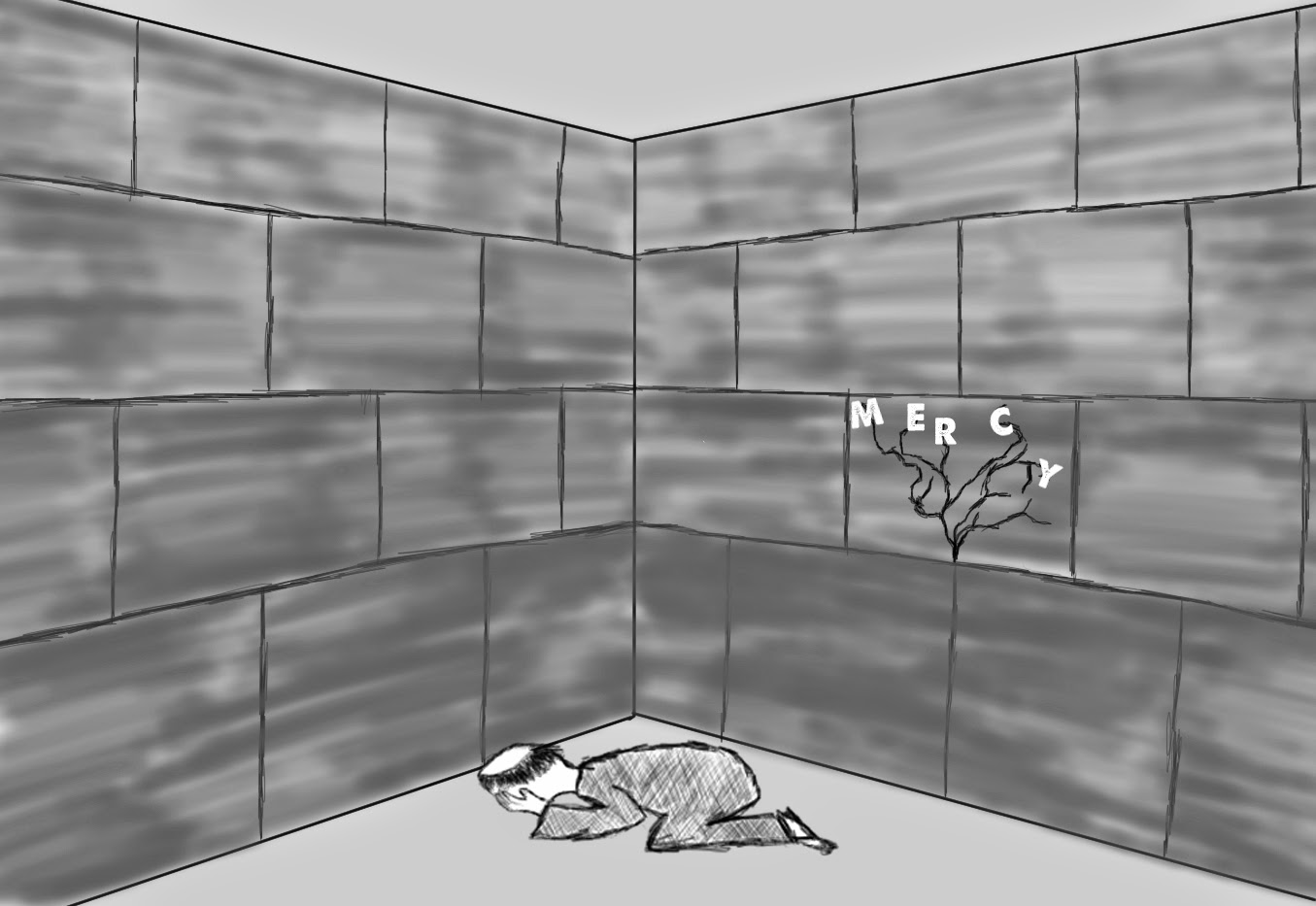

3For I recognize my rebellion;

it haunts me day and night.

Psalm 51 (NLT)

This week is the 497th anniversary of Martin

Luther sparking the Protestant Reformation.

It was October 31, 1517 that he nailed his 95 theses to the door of the

castle church in Wittenberg. He lit a

fire that embroiled Europe’s political, religious, and social landscape for

several centuries. But proceeding the momentous occasion were hours and hours

of tortuous solitude. Luther was well

known in his monastery for his time spent in isolated prayer. His prayers

tortured him, because he could not be rid of the guilt he felt over his

sin. He found himself in a monk’s cell

alone, but surrounded by his rebellion, haunted by his failures. He later described this period of his life as

agony. In his aloneness he could not

seem to escape his own darkness.

Luther lived in a time period where people stopped work

after sunset. They had no choice but to

slow-down and do something like read or spend time with family. But as a monk

he looked to prayer to pass the time.[1]

Take away the T.V., the radio, the screens, the pads, the tweets, the statuses,

the currents, the analog and digital ages, and what you have left is family,

pages, and your own soul.

Several years ago I preached a sermon on slowing down. I used the first few verses of the 23rd

Psalm, “The Lord is my shepherd; I shall not be in want. He makes me lie down in green pastures; He

leads me by still waters. He restores my

soul.” I told people that it’s important

to the vitality of our souls that we rest. Afterward a person accused me of

advocating laziness. I was shocked. How

can slowing down and laziness be synonyms in anyone’s mind? What’s more, this

person loved television!

It was already my conviction, but this interchange convinced

me that lurking deep in our subconscious is a dread, a terror that causes us to

cling to our responsibilities and to our modern web of entertainment. What are

we afraid of? On the one hand, I think

our relationships make us tremble.

Intimacy is a risk many are not willing to take. On the other hand,

there is the petrifying prospect of spending time alone with our own

souls. What might we find lurking in our darkness? We will, almost at all

cost, avoid being alone with our souls, lest we become tortured by our

brokenness. We don’t know what it would do to us to look our addictions in the

eye; to touch the bristly skin of our pride; to pass slowly enough to take in

the stench of our failures. So we

quickly pass by these dark shadows in bizarre busyness justified by the old

Protestant work ethic or the need to “rest” in the arms of Netflix’s latest

series release. We keep the noise of life turned up in order to drown out the

frail voices of our depravity’s ghosts.[2]

We often have no interest in being Luther, cloistered in our cell, haunted by

our rebellion.

David murdered Uriah so that he could take his wife and

cover up the fact that he had impregnated her.

The 51st Psalm tells us about the murderer’s emotions. He

cries out for God’s mercy.[3] At the same time he admits that the weight of

his sin torments him. It’s all he can

see and, like Luther, he wishes to be rid of it. If this is where solitude leads, who would

want to go there? None of us wants to be

in constant, overwhelming awareness of our faults. Perhaps the hurried distractions are healthy,

keeping us from running ourselves over with self-dread. I admit that this is a

tempting conclusion, but the reality is that hurriedness removes space for the

mercy of God.[4]

It is in the frightful moment of beholding the dregs of our

souls that we hear the sweet voice of mercy.[5] What good is the voice of mercy when we

obscure our need of it? We must find ourselves in silence, laying bare our

souls before God. This is not the moment

of salvation;[6]

this is the continuous walk of Christian transformation. We must make consistent space for the mercy

of God in our lives. What’s more, this

is where we learn compassion. Henri

Nouwen calls solitude “the furnace of compassion.”[7] In solitude we encounter our darkness; God

lifts the darkness with his soothing compassion on us. When we encounter that

compassion, knowing how badly we did not deserve it, we find ourselves

incapable of withholding it from anyone, because who could find that outdoes

our own brokenness? The opposite is perhaps also true: how can we be compassionate

if we withhold our soul from the moments of mercy? If we ourselves know not the

depth of God’s mercy how could we offer it to anyone? For we love, not of our

own design, but because he first loved us.

|

| This is either incredibly cheesy or awesome. |

So my challenge to you is to turn it all off. Find your monk’s cell, face the desolate

regions of your soul, lay them before God, hear his voice of mercy, and then

walk on, fully formed and shaped by the mercy of God.[8]

Come Lord Jesus, have

mercy on me, a sinner!

[1] It

probably isn’t fair to say this so casually.

He most surely did not think of prayer as a pastime, but more as a

struggle of devotion. All the same, when

the daylight fled and the darkness could only be pierced by candlelight he

found himself in prayer.

[2]

Depression seems to be the opposite of this, wherein the dark voices are

ceaseless, deafening, and indomitable. No amount of diversions can quiet them

or lessen their hold. Why/how this can

happen seems to be complicated, with at least some chemical explanations and

deeply unresolved pain. I’m no

psychologist, but I know that depression isn’t the person’s fault and I know

that it’s crazy difficult to counter. I also know that health can come again

through support and counseling. If this is where you are, talk to someone.

Let’s make sure that the haunting of your soul doesn’t keep you from the mental

health you deserve.

[3]

According to 2 Samuel 12:1-25, God does respond with mercy—probably not the

kind of mercy we’d prefer, but mercy as David understood it.

[4]

You probably don’t me to tell you, but it was out of his tortured solitude and

a reading of Romans that Luther discovered his doctrine of Grace.

[5]

You should know that I don’t think the soul is wholly evil. I’m not even just talking about

evil/sin. I’m thinking about the whole

breadth of human frailty. I also think

that in each soul there is a delicate, but lasting vestige of the image of God.

On the other hand, when I spend time in solitude I am almost always haunted by

my brokenness, not swept away by his image within me.

[6]

Though that moment bears certain similarities to the moment I’m describing.

[7]

One of the most important books I’ve ever read is, The Way of the Heart, by Nouwen. His basic point is that Christian

practice must lead to compassion.

[8] I

intend the next two Sundays and next week’s blog to think about what this

practically looks like.

Comments

Post a Comment